SPIN Magazine, February 3 2014, 9:23 AM ET

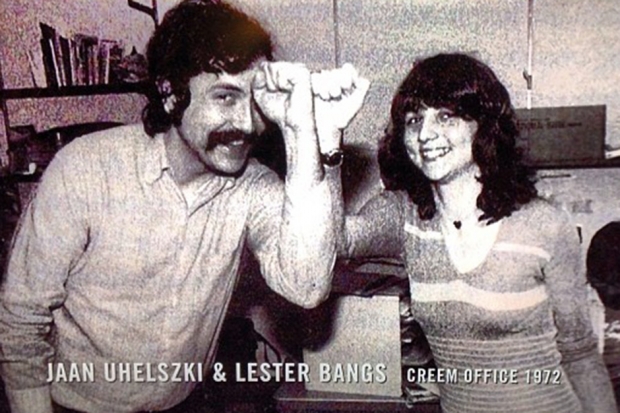

Music journalist Jaan Uhelszki was an editor at Creem magazine from 1971 to 1977. Her writing has appeared in Uncut, Mojo, Rolling Stone, Guitar World, and USA Today.

When Philip Seymour Hoffman died Sunday of an apparent overdose in his Greenwich Village apartment, it was like losing Lester Bangs all over again.

When Philip Seymour Hoffman died Sunday of an apparent overdose in his Greenwich Village apartment, it was like losing Lester Bangs all over again.

Bangs (who died in 1982) and I started at Creem magazine in Detroit on the very same day, and we occupied the same psychic space — sitting not three feet from each other — for the next six years. We went through a lot together, like members of a slightly dysfunctional family, which of course we were. He’d used my romantic history as fodder for an Eagles story, and I vowed to get him back and did. I ribbed him incessantly about the large protruding knot on the top of his head that he tried-but-failed to cover up with his unruly brown hair. It was if his brain was too big to be contained in one head and continued to grow outward, storing all that jazz and rock arcana that he carried around with him, kind of like an external hard drive.

We fought like siblings, mostly because he was so slovenly, rarely emptying his overflowing trash or throwing away the Coke cans with cigarette butts jammed into them. His typewriter was perennially covered with dirty T-shirts, girlie magazines, or wrappers from the tacos he so loved from Jack in the Box. He would pull one side of his mustache when he got anxious. He was a stereo hog, never letting any of us near the turntable; it had pride of place in an alcove above his desk, inaccessible to anyone but him.

Then there was his smell: not B.O., exactly, more like a ripe smell, like dirty feet or French cheese. The strange thing was, he never seemed to notice the stench.

I was witness to his fondness for Romilar and root-beer floats, was assaulted by Metal Machine Music for hours on end, and watched in utter wonder and envy as he would knock out a story in a couple of hours, like it was automatic writing. Lester Bangs wrote articles the way Keith Richards writes songs, with intuition and deliberation, and made it all look easy. And for him, I think it was.

Despite all his clownish behavior and bonhomie, he really got to the heart of a story — had an untethered imagination and, maybe most importantly, knew that what he did was a job. Lester and I used to have a saying at Creem: “Rock stars are not our friends,” and we’d remind each other every time we’d start to falter.

PHOTO BY CHARLEY AURINGER

PHOTO BY CHARLEY AURINGER

The thing is, Lester never really did, which is something that Cameron Crowe immortalized in his (primarily) autobiographical film Almost Famous, when Philip Seymour Hoffman, as Lester, tells William Miller, as Cameron, his theory of being uncool: “Oh man, you made friends with ’em. See, friendship is the booze they feed you. They want you to get drunk on feeling like you belong… Because they make you feel cool, and hey, I met you. You are not cool.”

Through all his shtick and over-alliterative tendencies, Lester possessed one of the greatest minds in rock criticism, and really knew how to get the story. He was fearless, and wasn’t afraid to tell any artist exactly what he thought — whether in print or in person. His criticism deeply hurt the usually unflappable Lou Reed, who told me years later that he felt Lester had struck him when he was down. “Lester loved me so much he had to attack me every day. You know, it was so weird, because it’s not like I didn’t have my own problems,” Reed told me in 2005. “That was some kind of weird … you know, somebody liked you so much that he just frothed at the mouth and tried to bite you.”

Lester provoked a food fight with Noddy Holder from Slade, dared Grace Slick to expose a breast for the magazine, and to this day, Ian Hunter holds a grudge against him over a bad review, having mistakenly thought that he’d get a pass just because the two of them were drinking buddies.

Before I’d met Philip Seymour Hoffman, I thought Cameron had made an odd choice when he cast the then-young actor, best known for his roles in Boogie Nights and Scent of a Woman, to play Lester. I thought Vince Vaughn would have made more sense. A young Rob Reiner. At least they both looked marginally like Lester. Philip Seymour Hoffman did not.

At least I didn’t think so until I sat across from Hoffman in a rather dark room conference room at a tony hotel on Madison Avenue on a crisp fall morning in 2000. I had been brought to the premier to do a piece on Almost Famous for Mojo. Along with a half dozen other journalists, I was scheduled to interview all the cast members. I had already been thoroughly bedazzled by Kate Hudson’s understated blond ambition, slightly annoyed by Billy Crudup’s earnestness, captivated by Jason Lee’s shape-shifting and, as always, by Crowe’s intelligence and boyish charm.

But nothing prepared me for what happened when Philip Seymour Hoffman sauntered into the room.

And “sauntered” is the accurate word. He had a low center of gravity, with a little hiccup in his walk, like someone who was trying to disguise a limp. If I’m being entirely honest, he walked a lot like Lester did, with a sort of rolling gait, like someone who had spent a lot of time aboard a ship (although if Lester had, he never mentioned it to me).

All the rest of the actors had been well dressed, attentive, eager to please, somehow. Certainly on their best behavior. Not Hoffman.

He wore a none-too-clean dark denim jacket, a wrinkled black T-shirt, a pair of weathered gray corduroy pants, and a pair of oxfords that your dad might own. His hair was long and unkempt; greasy, even. In fact, despite the fact that filming on Almost Famous had wrapped months earlier, he still looked exactly like the character he played in the film. A lot like Lester — except he smiled less.

Hoffman actually looked downright dangerous in his dirty denim. There was the sense that molecules just moved faster when he entered the room; you couldn’t take your eyes off of him. He’d mastered the kind of breezy drawl native to Southern California like Lester’s, but what struck me more was that he had brought his lunch and nonchalantly fielded questions as he ate. One of Lester’s more annoying habits was that he always talked with food in his mouth — and one that I’d almost forgotten about. That is, until I saw the same behavior in Hoffman.

Before Cameron Crowe started filming, I’d sent him a short list of behaviors specific to Lester — stuff that you observe when you live in close quarters with someone. He’d run up huge phone bills late at night to freelancers, or sometimes the people whose letters he printed in our Mail section. Sometimes we’d be in the office 20 hours a day, especially during deadlines, and when the pressure would get too much, we’d make an illicit run across the border to Windsor, Ontario, to get 222s — codeine pills you could buy over the counter there — and come back and write all night. I never thought Lester had a drug problem. I didn’t think I did either.

But I didn’t tell Cameron any of those things. I kept the list to stuff like personal hygiene, work ethos, favorite foods, or how when he was excited about something he was prone to grand, wild gestures, making big lavish circles in the air, or how he’d always pace when he talked on the phone. How he watched the soap opera All My Children religiously, owned a hermit crab named Spud, and that when things got bad, he used to say, “I could be selling shoes in El Cajon.” But I never told anyone about how he used to talk with his mouth full.

So on top of all the other similarities — and also, of course, how beautifully he’d channeled Lester in the film — it was a little unsettling when I watched Hoffman do the very same thing. I understood at that moment why people go to mediums to try to communicate with their deceased loved ones: It really felt like Lester was speaking through Philip Seymour Hoffman, and it made me a little nervous. I even thought about asking Hoffman questions that only Lester would know the answer to. I wish I had. For all of Hoffman’s gifts, I think his greatest was his mediumistic talent. How else could a beefy five-foot-10-inch guy play Truman Capote, who barely stood five-foot-three in his stocking feet, let alone win an Oscar for it?

That night, after I interviewed Hoffman, I went back to my hotel room and had a dream about Lester, something that happens with some regularity. In every dream, he isn’t dead, but instead has been hiding out somewhere. Waiting. This time, I asked him where he had been. He told me Florida. “I’ve just been waiting for you to get it right,” he told me.

Well, Philip Seymour Hoffman certainly got it right when he played Lester in Almost Famous. And maybe tonight I’ll go to sleep and bump into Lester and Philip Seymour Hoffman and Lou Reed arm wrestling and arguing about whether Jim Morrison is really a drunken buffoon posing as a poet and the Guess Who, who had the courage to actually be drunken buffoons, are the real poets. Or maybe the three of them are the real poets.